In this big post I try to pull together a theme to describe the last 20-30 years of investing.

One of the principle characteristics of this was the so-called 'great moderation' in inflation. This can be seen in the chart left since the early 1980s (courtesy of the

US Cleverland Fed.)

In the next chart we see that inflation is reasonably reflected in in the US 10 yr Treasury yield. Notice how yield rose from 1960s lows to peak in the early 1980s then fall through to now. Note also the price of a notional 10 yr US Treasury bond works in reverse and we had large bond rises. In fact bonds, particularly

zero-coupon long bonds have been a great investment.

We'll come to why at the end, but for now note in the chart below how bond prices have been rising as yields/inflation fall.

With inflation falling, shares increase in value. Why? Well a share price can be considered the current value (CV) of future cash flows from dividends over the long term. With falling inflation the discount rate (IR) falls, and the share CV becomes worth more. This is explained in '

What is NPV?' and the bond basics post. For now not that the S&P500 really took of when inflation started moderating as shown below:

Proof that much of the expansion in the S&P500 index was price to earning expansion is seen in the following long-term PE chart from

Bob Bronson. Note Bob's forecast into 2012.

The next asset class is housing and this two has boomed relative to fundamentals (rents). The chart below shows US and Australian prices in real terms, in nominal the price gains are greater. Since 2006-7 we have seen house prices globally correct (US, UK, Spain, New Zealand, Ireland, Canada and now Australia).

The last major asset class is commodities. The chart below is from

Martin Pring and shows commodity prices back to 1800. Martin suggests in a

presentation that as of July 08, commodities are close to peaking (if not already).

So over the last 20 years we have had every major asset class (bonds, equities, housing and commodities) boom and peak (possibly for commodities). Why?

The answer seems to be an amalgam of reasons as listed below, followed by commentary on whether it is likely to continue.

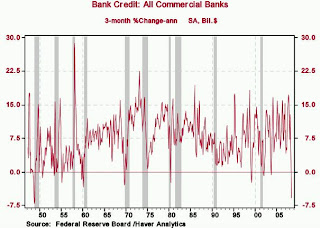

- Excess money supply (M0-M3). Not likely to continue with high inflation (M0) and commercial banks repairing balance sheets from massive credit losses (M1-M3). See posts on money here.

- Further interest rate falls. Not likely as inflation rises and bond holders demand higher returns (discount rates) and bid lower prices for bonds.

- Globalisation benefits. The growth of China Inc. was responsible lower prices everywhere on account of lower wages. However with China inflation rampant, and the Yuan appreciating against the US, China import prices are rising.

- Low commodity prices. Commodities rose out of mid-80s lows to the current high levels. Whilst they may correct, it will take significant global demand destruction to do so (and this only occurs in a global recession/depression).

- Inventory management gains. The smoothing of supply chains was responsible for reducing economic volatility. These gains have been made.

- Reduced wage bargaining power. The late 80s and 90s where eras of conservative pro-business/anti-worker global governments in which workers lost bargaining power. The swing has been back to the worker so there are no more wage gains to be made.

In short, I believe the inflationary aspects of excess money supply where masked by items 2-6 above allowing the great moderation. However, that excess money supply found it's was sequentially into bonds (lower interest rates), equities (2000 peak), property (2006 peak), and now commodities (2008 peak).

Consumers everywhere are maxed out. In the developed world consumers borrow costs, access to credit and higher living costs are forcing a dramatic reduction in spending amist falling housing prices. In the developing world high commodities dramatically affect the cost of living which is the major purchase item, killing any discretionary spending that may have existed.

What can turn the global economy? BRIC nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China) spending on infrastructure as part of nation building? Maybe, but these nations export economies will suffer the in the global downturn so at best nation-building will offset this.

Be sure to check the SEI global review for more information as events unfold.

At its simplest we consider the performance what we can control (our investment process), with that which we can't control (market outcome). A useful concept for making all sorts of decisions with imperfect information.

At its simplest we consider the performance what we can control (our investment process), with that which we can't control (market outcome). A useful concept for making all sorts of decisions with imperfect information.